you must follow

where it leads…

.

.

A long-lost play, newly found,

A killer who brings Shakespeare’s extravagant murders to life — and death,

And a race to find literary gold.

.

On the eve of the Globe’s production of Hamlet, Shakespeare scholar and theater director Kate Stanley’s eccentric mentor, Rosalind Howard, gives her a mysterious golden box, claiming to have made a groundbreaking discovery. Before she can reveal it to Kate, the Globe burns to the ground and Roz is found dead — murdered in the strange manner of Hamlet’s father. Inside the box Kate finds the first piece in a Shakespearean puzzle, setting her on a deadly, high-stakes treasure hunt.

From London to Harvard to the American West, Kate races to evade a killer and decipher a tantalizing string of clues, hidden in the words of Shakespeare, that may unlock literary history’s greatest secret.

“Glorious Fun” in More Than 25 Languages

Reviews

A “brainy romp” — “Carrell really kicks up her heels in…a weighty piece of scholarship packed into a feverishly paced action adventure…. The author’s wild storytelling style…clicks with the dashing Indiana Jones spirit of the adventure.”

—The New York Times

“High class fun” —Newsweek

“Glorious fun”

—The Independent (London)

“Utterly ingenious”

—The Guardian (London)

“Endlessly fascinating…. A lively intellectual romp”

—The Washington Post

“Plot twists worthy of The Da Vinci Code.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review).

“Set this book in the hands of readers and theater buffs who want smart excitement that’s not at all intimidating. They’ll join me in hoping that Carrell will give us what Will never will: sequels.”

—Galley Talk, Publishers Weekly

“An exciting, entertaining and surprisingly educational read just itching to make its big screen debut”

—Associated Press

“A gripping page-turner, an erudite account of contemporary Bard scholarship and the plays and poems that made Mr. Shakespeare, whoever he was, the man he is today. Perfect.”

—Daily Express (London)

“A hide-and-seek chase of murder and mayhem… Carrell omits [Dan Brown’s] ridiculous howlers but follows his penchant for twists, turns and incessant violence.”

—The Times (London)

“It’s The Da Vinci Code on steroids, and would be banned if it were an athlete…. An intelligent, thought-provoking, highly readable and extremely fast-paced whodunnit spanning four centuries.”

—Daily Sport (London)

“Literary sensation of the year”

—The Bookseller (UK)

A “notable debut”

—USA Today

One of “10 fiction titles you won’t want to miss” this fall.

—The Houston Chronicle

“Attention conspiracy theorists: Take a break from Templar mysteries and try some poetry for a change…. plenty of globe-trotting action along with the literary clues.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Grand and harrowing”

—Tucson Weekly

“Highly entertaining… Sure to spark rousing discussion in book circles”

—Bookreporter.com

“Kept me up long into the night, eager to take that next turn in the plot”

—Book Buzz

Excerpt: Prologue (A Glimpse of Shakespeare's World)

June 29, 1613

From the river, it looked as if two suns were setting over London.

One was sinking in the west, streaming ribbons of glory in pink and melon and gold. It was the second sun, though, that had conjured an unruly flotilla of boats and barges, skiffs and wherries, onto the dark surface of the Thames: Across from the broken tower of St. Paul’s, a sullen orange sphere looked to have missed the horizon altogether and rammed itself into the southern bank. Hunkering down amid the taverns and brothels of Southwark, it spiked vicious blades of flame at the night.

It wasn’t, of course, another sun, though men who fancied themselves poets sent that conceit rippling from boat to boat. It was – or had been – a building. The most famous of London’s famed theaters – the hollow wooden O, round seat of the city’s dreams, the great Globe itself – was burning. And all of London had turned out on the water to watch.

The earl of Suffolk included. “Upon Sodom and Gomorrah, the Lord rained down fire from heaven,” purred the earl, gazing south from the floating palace of his private barge. In his office of lord chamberlain of England, Suffolk ran the king’s court. Such a disaster befalling the King’s Men – His Majesty’s own beloved company of actors who not only played at the Globe when they weren’t playing at court, but who owned the place – might have been expected to disturb him. To scuff, at the very least, the sheen of his pleasure. But the two men sitting with him beneath the silken awning gave no sign of surprise as they sipped wine, contemplating the catastrophe.

Their silence left Suffolk unsatisfied. “Gorgeous, isn’t it?” he prompted.

“Gaudy,” snapped his white-haired uncle, the earl of Northampton, still lean and elegant in his mid-seventies.

The youngest of the three, Suffolk’s son and heir, Theophilus, Lord Howard de Walden, leaned forward with the intensity of a young lion eyeing prey. “Our revenge will burn even brighter in the morning, when Mr. Shakespeare and company learn the truth.”

Northampton fixed his great-nephew with hooded eyes. “Mr. Shakespeare and his company, as you put it, will learn nothing of the kind.”

For a heartbeat, Theo sat frozen in his great-uncle’s stare. Then he rose and hurled his goblet forward into the bottom of the barge, splattering servants’ saffron-yellow liveries with dark leopard spots of wine. “They have mocked my sister on the public stage,” he cried. “No amount of conniving by old men shall deprive my honor of satisfaction.”

“My lord nephew,” said Northampton over his shoulder to Suffolk. “With remarkable consistency, your offspring exhibit an unfortunate strain of rashness. I do not know whence it comes. It is not a Howard trait.”

His attention flicked back to Theo, whose right hand was closing and opening convulsively over the hilt of his sword. “Gloating over one’s enemies is a simpleton’s revenge,” said the old earl. “Any peasant can achieve it.” At his nod, a servant offered another goblet to Theo, who took it with poor grace. “Far more enthralling,” continued Northampton, “to commiserate with your foe and force him to offer you thanks – even as he suspects you, but cannot say why.”

As he spoke, a small skiff drew up alongside the barge. A man slid over the rail and glided toward Northampton, shunning the light like a wayward shadow slinking home to its body. “Anything worth doing at all, as Seyton here will tell you,” continued Northampton, “is worth doing exquisitely. Who does it is of little consequence. Who knows who did it is of no consequence at all.” Seyton knelt before the old earl, who put a hand on his shoulder. “My lord of Suffolk and my sulking great-nephew are as curious as I am to hear your report.”

The man cleared his throat softly. His voice, like the rest of his clothing and even his eyes was of an indeterminate hue between gray and black. “It began, my lord, when the players’ gunner took sick unexpected this morning. His substitute seems to have loaded the cannon with loose wadding. One might even suspect it had been soaked in pitch.” His mouth curved in what might have been a sly smile.

“Go on,” said Northampton with a wave.

“The play this afternoon was a relatively new one, called All is True. About King Henry the Eighth.”

“Great Harry,” murmured Suffolk, trailing one hand in the water. “The old queen’s father. Dangerous territory.”

“In more ways than one, my lord,” answered Seyton. “The play calls for a masque and parade, including a cannon salute. The gun duly fired, but the audience was so taken with the flummery onstage that no one noticed sparks landing on the roof. By the time someone smelled smoke, the roof thatch was ringed with fire, and there was nothing to do but flee.”

“Casualties?”

“Two injured.” His eyes flickered toward Theo. “A man called Shelton.”

Theo started. “How?” he stammered. “Hurt how?”

“Burned. Not badly. But spectacularly. From my perch – a fine one, if I may say so – I saw him take control of the scene, organizing the retreat from the building. Just when it seemed everyone had got out, a young girl appeared at an upper window. A pretty thing, with wild dark hair and mad eyes. A witch child, if ever I saw one.

“Before anyone could stop him, Mr. Shelton ran back inside. Minutes passed, and the crowd began to weep, when he leapt through a curtain of fire with the girl in his arms, his backside aflame. One of the Southwark queens tossed a barrel of ale at him, and he disappeared again, this time in a cloud of steam. It turned out that his breeches had caught fire, but he was, miraculously, little more than scorched.”

“Where is he?” cried Theo. “Why have you not brought him back with you?”

“I hardly know the man, my lord,” demurred Seyton. “And besides, he’s the hero of the hour. I could not disentangle him from the crowd with any sort of discretion.”

With a glance of distaste at his great-nephew, Northampton leaned forward. “The child?”

“Unconscious,” said Seyton.

“Pity,” said the old earl. “But children can prove surprisingly strong.” Something wordless passed between the old earl and his servant. “Perhaps she’ll survive.”

“Perhaps,” said Seyton.

Northampton sat back. “And the gunner?”

Once again, Seyton’s mouth curved in the ghost of a smile. “Nowhere to be found.”

Nothing visibly altered in Northampton’s face; all the same, he radiated dark satisfaction.

“It’s the Globe that matters,” fretted Suffolk.

Seyton sighed. “A total loss, my lord. The building is engulfed, the tiring-house behind it, with the company’s store of gowns and cloaks, foil jewels, wooden swords and shields… all gone. John Hemminges stood in the street, blubbering for his sweet palace of a playhouse, his accounts, and most of all, his playbooks. The King’s Men, my lords, are without a home.”

Across the water, a great roar shot skyward. What was left of the building imploded, collapsing into a pile of ash and glimmering embers. A sudden hot gust eddied across the water, swirling with a black snowfall of soot.

Theo howled in triumph. Beside him, his father ran a fastidious hand over his hair and beard. “Mr. Shakespeare will never again so much as jest at the name of Howard.”

“Not in my lifetime, or in yours,” said Northampton. Silhouetted by the fire, heavy eyelids drooping over inscrutable eyes, his nose sharpened by age, he looked the very essence of a demonic god carved from dark marble. “But never is an infinite long time.”

—Reprinted from Interred With Their Bones by Jennifer Lee Carrell By permission of Plume, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © 2007 by Jennifer Lee Carrell. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

First Chapter (Meet Kate Stanley)

Chapter One

June 29, 2004

We are all haunted. Not by unexplained rappings or spectral auras, much less headless horsemen and weeping queens — real ghosts pace the battlements of memory, endlessly whispering, Remember me. I began to learn this sitting alone at sunset on a hill high above London. At my feet, Hampstead Heath spilled into the silver-gray sea of the city below. On my knees glimmered a small box wrapped in gold tissue and ribbon. In the last rays of daylight, a pattern of vines and leaves, or maybe moons and stars swam beneath the surface of the paper.

I cupped the box in both palms and held it up. “What’s this?” I’d asked earlier that day, my voice carving through the shadows of the lower gallery at the Globe Theatre, where I was directing Hamlet. “An apology? A bribe?”

Rosalind Howard, flamboyantly eccentric Harvard Professor of Shakespeare — part Amazon, part earth mother, part gypsy queen — had leaned forward intently. “An adventure. Also, as it happens, a secret.”

I’d slipped my fingers under the ribbon, but Roz reached out and stopped me, her green eyes searching my face. She was fiftyish, with dark hair cut so short as to be boyish; long shimmering earrings dangled from her ears. In one hand, she held a wide-brimmed white hat set with peonies in lush crimson silk — an outrageous affair that seemed to have been plucked from the glamour days of Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly. “If you open it, you must follow where it leads.”

Once, she’d been both my mentor and my idol, and then almost a second mother. While she played the matriarch, I’d played the dutiful disciple — until I’d decided to leave academics for the theater three years before. Our relationship had frayed and soured even before I left, but my departure had shorn it asunder. Roz made it clear that she regarded my flight from the ivory tower as a betrayal. Escape was how I thought of it; absconded was the term I’d heard that she favored. But that remained hearsay. In all that time, I’d heard no word of either regret or reconciliation from her, until she’d shown up at the theater without warning that afternoon demanding an audience. Grudgingly, I’d cut a fifteen-minute break from rehearsal. Fifteen minutes more, I told myself, than the woman had any right to expect.

“You’ve been reading too many fairy tales,” I’d answered aloud, sliding the box back across the table. “Unless it leads straight back into rehearsal, I can’t accept.”

“Quicksilver Kate,” she’d said with a rueful smile. “Can’t or won’t?”

I remained stubbornly mute.

Roz sighed. “Open or closed, I want you to have it.”

“No.”

She cocked her head, watching me. “I’ve found something, sweetheart. Something big.”

“So have I.”

Her gaze swept around the theater, its plain oak galleries stacked three stories high, curving around the jutting platform of the stage so extravagantly set into gilt and marble backing at the opposite end of the courtyard. “Quite a coup, of course, to direct Hamlet at the Globe. Especially for a young American — and a woman to boot. Snobbiest crowd on the planet, the British theater. Can’t think of anyone I’d rather see shake up their insular little world.” Her eyes slid back toward me, flickering briefly over the gift perched between us. “But this is bigger.”

I stared at her in disbelief. Was she really asking me to shake the dust of the Globe from my feet and follow her, based on nothing more than a few teasing hints and the faint gravitational pull of a small gold-wrapped box?

“What is it?” I asked.

She shook her head. “‘Tis in my memory locked, and you yourself shall keep the key of it.”

Ophelia, I’d groaned to myself. From her, I’d have expected Hamlet, the lead role, and center stage every time. “Can you stop speaking in riddles for two minutes strung together?”

She motioned toward the door with a small jerk of her head. “Come with me.”

“I’m in the middle of rehearsal.”

“Trust me,” she said, leaning forward. “You won’t want to miss being in on this.”

Rage flared through me; I rose so quickly I knocked several books off the table.

The coy teasing drained from her eyes. “I need help, Kate.”

“Ask someone else.”

“Your help.”

Mine? I frowned. Roz had any number of friends in the theater; she would not need to come to me for questions about Shakespeare on the stage. The only other subject she cared about and that I knew better than she did stretched between us like a minefield: my dissertation. I had written on occult Shakespeare. The old meaning of the word occult, I always hastened to add. Not so much darkly magical, as hidden, obscured, secret. In particular, I’d studied the many strange quests, mostly from the nineteenth century, to find secret wisdom encoded in the works of the Bard. Roz had found the topic as quirky and fascinating as I did – or so she had claimed in public. In private, I’d been told, she had torpedoed it, dismissing it as beneath true scholarship. And now she wanted my help?

“Why?” I asked. What have you found?”

She shook her head. “Not here,” she said, her voice dipping into a low, urgent hush. “When will you finish?”

“About eight.”

She leaned closer. “Then meet me at nine, at the top of Parliament Hill.”

It would be dusk by then, in one of the loneliest spots in London. Not the safest time to be out on the Heath, but one of the most beautiful. As I hesitated, something that might have been fear flickered across Roz’s face. “Please.”

When I made no answer, she stretched out her hand, and for a moment, I thought she’d snatch back the box, but instead she reached up to touch my hair with one finger. “Same red hair and black Boleyn eyes,” she murmured. “You know you look especially royal when angry?”

It was an old tease — that in certain moods, I looked like the queen. Not the present Elizabeth, but the first one. Shakespeare’s queen. It wasn’t just my auburn hair and dark eyes that did it, either, but the slight hook in my nose, and fair skin that freckled in the sun. Once or twice, I’d glimpsed it in the mirror myself — but I’d never liked the comparison or its implications. My parents had died when I was fifteen, and I’d gone to live with a great-aunt. Since then, I’d spent much of my life in the company of autocratic older women, and I’d always sworn I would not end up like them. So I liked to think I had little in common with that ruthless Tudor queen, save intelligence, maybe, and a delight with Shakespeare.

“Fine,” I heard myself say. “Parliament Hill at nine.”

A little awkwardly, Roz lowered her hand. I think she couldn’t quite believe I’d given in so easily. Neither could I. But my anger was sputtering out.

The intercom crackled. “Ladies and gents,” boomed the voice of my stage manager, “places in five minutes.”

Actors began flocking into the bright glare of the courtyard. Roz smiled and stood. “You must go back to work, and I must simply go.” In a rush of nostalgia, I glimpsed a ghost of the old wit and spark between us. “Keep it safe, Katie,” she’d added with one last nod at the box. Then she’d walked away.

Which was how I came to be sitting on a bench up on Parliament Hill at the end of the day, doing what I’d once sworn I’d never do again: waiting for Roz.

I stretched and considered the world spread out in the distance. Despite the two fanged towers of Canary Wharf to the east and another set midtown, from this height London looked a gentle place, centered on the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral like a vast downy nest harboring one luminous egg. In the last hour, a steady trickle of people had passed by on the path below. Not one of them had turned up toward me, though, marching through the grass with anything like Roz’s arrogant step. Where was she?

And what could she be hoping for? No one in their right mind could imagine that I’d give up directing Hamlet at the Globe. Not yet thirty, American, and trained first and foremost as a scholar, I figured I was pretty much the toxic negative of whatever the gods of British theater might imagine as ideal clay for fashioning a director. The offer to take on Hamlet — the finest jewel in the British theatrical crown — had seemed a miraculous windfall. So much so, that I’d saved the voice mail from the Globe’s artistic director, spelling it out. I still played his manic, staccato voice back every morning, just to make sure. In that state of mind, I didn’t much care if the box in my lap held a map of Atlantis or the key to the Ark of the Covenant. Surely even Roz at her most self-involved would not expect me to exchange my title of “Master of Play” for whatever mystery, large or small, she’d handed into my keeping.

The show opened in three weeks. Ten days after that would come the worst part of life in the theater. As director, I’d have to stop hovering, tear myself from the camaraderie of cast and crew, and slink out, leaving the show to the actors. Unless I’d lined up something else to do.

The box sparkled on my knee.

Yes, but not yet, I could tell Roz. I’ll open your infernal gift when I’m finished with Hamlet. If, that is, she bothered to show up for any answer at all.

At the bottom of the hill, lights kindled as night crept through the city in a dark tide. The afternoon had been hot, but the night air was growing cool, and I was glad I’d brought along a jacket. I was putting it on when I heard a twig snap behind me, somewhere up the hill; even as I heard it, the prickle of watching eyes washed down my back. I stood and whirled, but darkness had already settled thickly into the grove fringing the hilltop. Nothing moved but what might be wind in the trees. I took a step forward. “Roz?”

No one answered.

I turned back, scanning the scene below. No one was there, but gradually I became aware of movement I had not noticed before. Far below, behind St. Paul’s, a pale column of smoke was spiraling lazily into the sky. My breath caught in my throat. Behind St. Paul’s, on the south bank of the River Thames, sat the newly rebuilt Globe with its walls of white plaster criss-crossed with oak timbers, its roof prickly with flammable thatch. So flammable, in fact, that it had been the first thatched roof allowed in London since the Great Fire of 1666 had burned itself out almost three and a half centuries ago, leaving the city a charred and smoking ruin.

Surely the distance was deceptive. The smoke might be rising five miles to the south of the Globe, or a mile to the east.

The column thickened, billowing gray and then black. A gust of wind took it up, fanning it out; at its heart winked an ominous flicker of red. Shoving Roz’s gift into the pocket of my jacket, I strode downhill. By the time I reached the path, I was running.

—Reprinted from Interred With Their Bones by Jennifer Lee Carrell By permission of Plume, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © 2007 by Jennifer Lee Carrell. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Reading Group Guide

Find an interview with suggested discussion questions HERE.

Listen to Jennifer

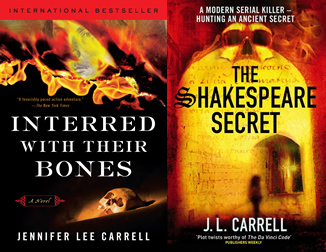

The Reduced Shakespeare Company Podcast #91: The Shakespeare Secret

Interview by Austin Tichenor

April 25, 2008

By permission of The Reduced Shakespeare Company

The evil that men do lives on,

The good is oft interred with their bones.