Smithsonian, August, 1998

Sometime late in 1863, a tall, thin man rode out of an Army camp in the Wyoming territory and headed across the prairie. He was just under 60 years old, one of the greatest scouts and Indian fighters, a man from whom Kit Carson took orders. It was the wild places that Jim Bridger liked best; following strange tales into the unknown, he was probably the first white man to see the Great Salt Lake. At that moment, however, he was headed toward people, not away from them. Not too far off, the Oregon Trail snaked westward across the landscape. Traffic had dwindled by 1863, but this trail still ranked as a highway by the standards of men such as Bridger; you could hardly follow its hard-packed earth so much as a day without running across somebody. That was exactly why Bridger was headed there.

He was looking to do some trading. What he had to offer was a yoke of cattle, then worth about $125, or almost a month of his wages as an Army scout. What Bridger wanted, and what he thought he could get from a wagon train, was a book. And not just any book, but the book that an Army officer had told him was the best ever written. He wanted Shakespeare.

Bridger’s quest might sound unlikely, but all over the American West trappers, cowboys, miners, outlaws, proper ladies, prostitutes and Army officers regarded Shakespeare with a familiar ease and delight that might astonish the average American in the late 20th century. The history of the West, in fact, is a history of playing Shakespeare, of playing with Shakespeare, in what now may seem peculiar places and surprising ways.

The Oregon Trail

Bridger, for instance, got what he wanted: someone, going west in wagons that could hold only the most necessary and precious possessions, had brought along a volume of Shakespeare. Out on the prairie, that someone judged the book not quite so precious as a yoke of cattle. For the additional sum of $40 per month, Bridger hired a German boy to read his new book to him. For though he could speak English, French, Spanish and a dozen Indian languages, and though he could draw, freehand, highly accurate maps of the West, Bridger could not read.

He could listen, however, and listen he did. Bridger was already well known as a storyteller. Because he sometimes embellished the already extraordinary natural marvels of the West, and because writers and others made up wild tales and attributed them to him, he also had a growing though undeserved reputation as a liar. That winter, however, he added to his repertoire: from then on he could quote Shakespeare at length. The prospect of an old mountain man spouting Shakespeare now seems more fantastic than the same man spinning tales about salt lakes, glass mountains and hot- and cold-running rivers. Nonetheless, Bridger came to know Shakespeare’s cadences of speech so well that his own speech could slide through the poet’s rhythms, especially the insults. One of Bridger’s tricks was to insert his own oaths into Shakespeare, so that his audience did not know where the playwright stopped and the mountain man began.

In search of the places that Bridger and others once took Shakespeare, I find myself heading off the main roads, and then off-road altogether. Up in Colorado’s Gunnison County, I wind north through a wide valley filled with quaking aspen and tall trumpet flowers. Passing beneath the mountain whose sky-hungry spires gave the town of Gothic its name, the road bounces up over a pass and creeps into a darker forest of pine and spruce. This is country that in summer is still best covered on horseback.

But I am horseless, so when I give up on the car, I set off on foot. For somewhere up here, say century-old documents that briefly sound more like The Hobbit than legal records, “at the foot of the Treasure Mountain” there lies a mine called Shakespeare.

Treasure Mountain, Colorado

It was not a spectacularly rich mine, but it was respectable. Two years after it was located in 1879, the last of its original owners, John Blewett, sold out for $30,000. Blewett may have revered the Bard, but he didn’t spend all his free time reading. Having sold his rights to the mine, he promptly made his way down to Gothic and won a shooting contest.

The name is scattered all over the West: “Shakespeare” names a town and a canyon in New Mexico, a mountaintop in Nevada, a reservoir in Texas and a glacier in Alaska. But it was the miners who most often staked Shakespeare to the earth. Nineteenth-century claims called Shakespeare dotted the landscape of Colorado and spilled over into Utah. The mines that still scar Western mountains now seem a curious honorific for a great poet. Yet, Shakespeare takes his place among heroes and sweethearts.

In their quest for distinctive names, the miners delved into the Bard’s stories. Colorado sports mines called Ophelia, Cordelia and Desdemona. There is even a “Timon of Athens,” revealing that some prospectors dug into remote corners of Shakespeare as well as remote corners of North America, because Timon is one of Shakespeare’s least-known plays. It is a fitting name for a mine, though, because the play’s hero — a mad, bankrupt misanthrope — accidentally discovers “yellow, glittering, precious gold” while digging in the forest for roots.

I did not, in the end, find the valley where modern survey maps and ancient mining records suggest the remains of Blewett’s mine lie. Far to the south, however, I did find an entire town called Shakespeare. By 1879, Ralston, New Mexico, was short on respectability, having been the site of a diamond-mine hoax that had produced a bank failure, a suicide and substantial losses for investors. In April of that year, therefore, Col. William G. Boyle renamed the town Shakespeare. He already owned the Stratford Hotel, and Main Street was familiarly known as Avon Avenue; soon after, Boyle organized the Shakespeare Gold and Silver Mining and Milling Company. The townsmen joined the trend, organizing the Shakespeare Guards to defend the place against Apache raids.

Shakespeare was more than a name to miners, however. During the gold rush, playgoing had a prominent place among the drinking, gambling and carrying on that was the miners’ usual relief from hard and dangerous work. From Colorado to California, theaters that played Shakespeare more than any other playwright perched just across the street, or sometimes right upstairs, from the saloons and gambling halls that were sometimes brothels as well. All over the West, towns built elaborate gilt-and-plush theaters grandiosely called opera houses. A few of these jewel-box theaters still survive in former boomtowns such as Nevada City, California; Tombstone, Arizona; and Aspen, Central City, and Leadville, Colorado. When theaters weren’t available people gathered in saloons, hotel hallways or even tents to watch actors play on stages made of packing boxes or boards laid across billiard tables and lit by kerosene lanterns; in Calaveras County, California, actors performed on the stump of a giant redwood.

The greatest actors from the Eastern Seaboard played to packed houses on these stages. Edwin Booth (elder brother of John Wilkes Booth) played his first Shakespearean leads on the magnificent and makeshift stages of California.

From left to right: John Wilkes, Edwin, and their father Junius Brutus Booth in Julius Caesar, 1864

That this caliber of actor regularly appeared in such venues might have been for adventure’s sake, but it was also partly because there was fame and wealth to be found among the miners. In the 1850s, top actors could earn up to $3,000 a week in San Francisco; the best theaters in the East were offering only a tenth as much. But it was up in the boisterous camps that the actors struck gold. In places with names like Rattlesnake, Rough and Ready, Git-up-and-Git and Hangtown, theater tickets were bought with gold dust, and cheering miners tossed nuggets and bags of gold dust onto the stage at curtain call.

The first people to carry Shakespeare into the West were trappers, who threaded their way into the Rockies along the rivers on their quest for beaver. Mountain men were legendary for gathering around campfires to tell bear stories both hair-raising and hilarious. According to the recollections of trappers Joe Meek and Bill Hamilton, however, though they might indeed be swapping bear stories, they might just as well be sharing a little Shakespeare. Or they might even be doing both: after all, the Bard’s most infamous stage direction, from The Winter’s Tale, is “Exit pursued by a bear.”

Alfred Jacob Miller, Moonlight — Camp Scene, 1858-60, Watercolor on paper

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

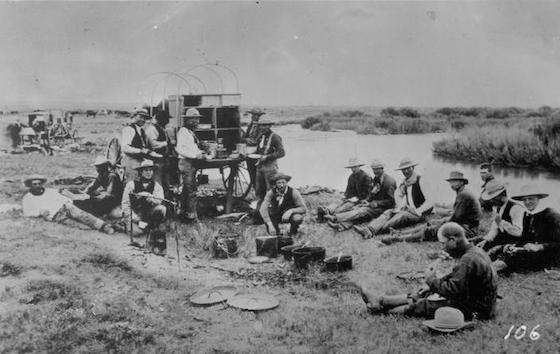

On the frontier, Shakespeare was not “Art” to be adored in silent, solitary reading; Shakespeare was a set of stories to be told aloud, language to be tasted, toyed with, tossed about over a campfire. Bridger is a case in point: after he bought his precious book, it never seems to have occurred to him to learn to read. What he wanted from the book was specifically what was in it. Like Bridger, other Westerners might get their Shakespeare out of books, but in books they did not let him stay. The 19th century was an age of oral storytelling and public speaking; if Shakespeare was taught at all, it was taught as oratory and recitation — then parts of the most basic schooling. Since Shakespeare was seen and heard more than read, no one needed much, if any, formal education to have at least a passing acquaintance with the works. Montana rancher Philip Ashton Rollins said that many ranch owners brought Shakespeare west with them. It was not unusual to see “a bunch of cowboys sitting on their spurs listening with absolute silence and concentration while somebody read aloud.” Further, Shakespeare was popular because of the poetry, not in spite of it. After listening to the blood and thunder “dogs of war” speech in Julius Caesar, one top hand told Rollins, “Gosh! That fellow Shakespeare could sure spill the real stuff. He’s the only poet I ever seen what was fed on raw meat.”

Roundup Camp, Wyoming, 1880s

Among Westerners, the most popular Shakespearean plays were the tragedies and epic histories, with Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet heading the list. Westerners, however, were not silenced into tongue-tied awe by high tragedy. Like Bridger — who was once heard to say that Falstaff (or “Mr. Full-stuff”) liked beer a little too much for his own good and might have been better off with bourbon — cowboys, outlaws, miners and trappers embraced Shakespeare. They brought it to life, retelling it in a mix of remembered poetry and the teller’s own salty language.

Along with the enthusiasm came irreverence. It was common in 19th-century American theater to follow the main play, no matter how profound, with a comic song, a dance, and finally a farce in which the principal actors often reappeared. In Denver in 1859, a troupe followed Richard III with a polka and a farce called Luck in a Name; in San Francisco, King Lear was once followed by a dancing horse named Adonis. Sometimes the kind of mischief that led Bridger to alter Shakespeare’s oaths took over the stage completely. Audiences loved farces with titles like Hamlet and Egglet and Julius Sneezer, and burlesque Shakespeare was popular minstrel fare.

Westerners also delighted in creative casting. In Army camps, all-male performances were not uncommon. In Texas on the eve of the Mexican War, Lieut. Ulysses S. Grant was drafted into the role of Desdemona because he supposedly looked the part. Before opening night, however, his superiors had to send off to New Orleans for a real woman, because Grant failed to show “the proper sentiment.” Great actresses playing Shakespearean heroes in serious productions were ticket-selling curiosities. The women’s success led to the brief vogue of having little girls play the major tragic roles; thus did Anna Maria Quinn, age 6, play Hamlet to a mostly adult male audience at San Francisco’s Metropolitan Theatre in 1854. In Deer Lodge, Montana, on the other hand, miners and cowboys were treated to the spectacle of an actress playing Juliet with an imitation Romeo: a “blockhead in every respect” reported one witness delighted by the wooden dummy outfitted with wig and red cambric gown, and even more by the parodic performance that followed.

Because Shakespeare — as story or poetry or theater — was shared by so many people, it became a kind of imaginative meeting place. The readings organized by Bridger, for example, brought together an illiterate mountain man, a German boy and the well-educated Army officer who had first recommended the Bard. In the theater, there was no assumption that Shakespeare should be delivered in the plummy tones of the British upper class; audiences flocked to hear their favorite actors play Shakespeare in English heavily laden with German, Polish, French and Italian accents in addition to regional British, American and Australian inflections.

For all the intensity of their love affair with Shakespeare, Westerners had no monopoly on it. In 1849, what is still one of the bloodiest riots in American history broke out in New York City — over styles of acting Shakespeare. A vigorous style was said to be democratic and American while more cerebral acting was said to be aristocratic and English. Enraged by a supposedly elitist performance of Macbeth, a crowd of 10,000 surged outside the Astor Place Opera House (Smithsonian, October 1985). When the mob turned from hurling insults to hurling paving stones, the New York militia opened fire, shooting directly into the crowd at least 22 people died and 150 others were wounded.

The Astor Place Riot, New York City, 1849

As the frontier straggled westward, the differences that had chafed in crowded New York were stretched out across the continent; Westerners favored flamboyant acting while disdaining polished elegance as snobbish and Eastern. Less than a year after the Astor Place Riot, Shakespeare arrived along with the forty-niners in the California goldfields, and by 1856, the Californians, too, were brawling over Shakespeare. In the West, though, it was not politics but the combination of characters acting badly and actors acting badly that provoked riots.

At a Sacramento performance of Richard III, the audience began to get restive in the face of Richard’s mounting evil and the actor’s obvious incompetence. When at last Richard stabbed one of his victims in the back, the audience began tossing any and all handy garbage onto the stage: bags of flour and soot, old vegetables, a dead goose. At the request of the stage manager, the audience allowed Richard to reappear, but when he placed his sword in the hands of Lady Anne during the wooing scene, “one half the house, at least, asked that [the sword] might be plunged in his body,” the Sacramento Union reported. The actor was finally driven from the stage by a “well directed pumpkin… with still truer aim, a potato relieved him of his cap, which was left upon the field of glory, among the cabbages.”

In their noisy displays of pleasure and displeasure, Western audiences preserved and even heightened an exuberant tradition of theatergoing dating back to the Elizabethan audiences that Shakespeare knew. They expected to enter into the spirit of play, and the same enthusiasm that could produce showers of either rotten vegetables or gold dust also provoked, at less frenzied moments, stamping, cheering, whistling and hooting, as well as quips and running commentary on the play, the players and the production.

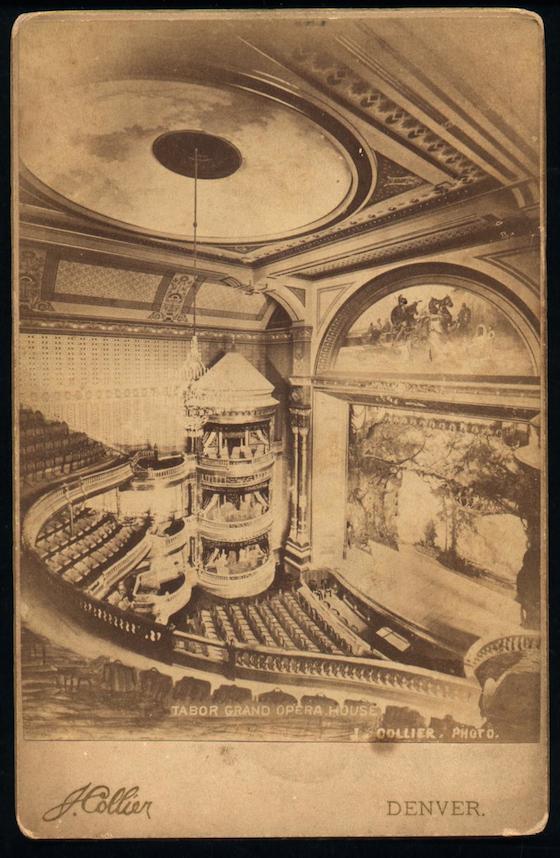

This freewheeling audience participation had once been common all over America, but in the late 19th century Shakespearean theater was fast becoming an elite and stately affair in the East and in Europe. Western audiences preserved longer their right to play during the play. Appearing as Othello in 1886, Tommaso Salvini was so disturbed by the laughter and popping of champagne corks coming from “Silver King” Horace Tabor’s personal box in Denver’s Tabor Grand Opera House that he sent a note up during intermission threatening to stop the play if things in Box A did not quiet down. “My theater is a playhouse as much for the audience as for the actors,” Tabor reportedly bellowed back. “If that Eyetalian wants to pray,” Tabor fumed, “let him go to church.”

The Tabor Grand Opera House, Denver, Colorado. Photo by J. Collier

Nonetheless, changing attitudes eventually traveled westward; Lawrence Levine of George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia, has speculated that Shakespeare’s fall from popularity in America was caused by large-scale shifts in ideas about what is entertainment and what is art. When Shakespeare stopped being story and began to be art, it began to seem distant; when accuracy became more important than entertainment, it became boring; and when the language of Shakespeare ceased to be commonly heard aloud, it began to seem difficult. Beyond doubt, however, changing attitudes toward Shakespeare have resulted in what now looks like a paradox: Shakespeare’s popularity in the American West dwindled as the West was settled and ceased to be wild.

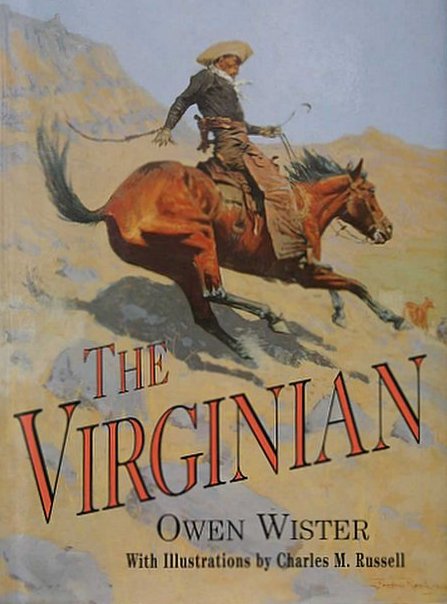

Shakespeare has not, however, disappeared from the West without a trace: it still shapes the myth of what we think the West was, or ought to have been. The novel that established the genre of the western, Owen Wister’s The Virginian (published in 1902), features an aloof hero who is a dead shot and a deeply honorable man. He is also prone to quoting Shakespeare; the poet’s lyricism captivates him. “The singing masons building roofs of gold,” he says at one point, quoting from King Henry V. “Ain’t that a fine description of bees a-workin’?…Puts ’em right before yu’, and is poetry without bein’ foolish.” Following the novelists, Hollywood, too, has borrowed from Shakespeare in shaping our idea of the West that was. The film Broken Lance (1954), for instance, tells King Lear in the guise of a western, while Jubal (1956) reshapes Othello.

Today up in Leadville, you can, as I did, climb onto the stage of the Tabor Opera House and stand in front of the painted scenery that once backed Romeo and Juliet. Facing the plush seats that curve toward you, you can let your voice roll out into the hushed and waiting darkness on the cadences of Shakespeare. In the ghost town of Shakespeare, you can, as I did, duck out of the New Mexico sun into the shade of the Stratford Hotel’s long narrow dining room, where the desert wind will send the fine silt of crumbling adobe drifting over your skin and through your hair; there you can listen to the stories that the town’s present owners, Janaloo Hill and Manny Hough, have spent a lifetime collecting from old-timers.

The Stratford Hotel in Shakespeare, New Mexico. Photo by Jennifer Lee Carrell

Yet Shakespeare is more than a ghost in the West. After the Bard ceased to be part of their everyday life, Westerners began to pioneer the Shakespeare festival. Every summer tourists descend upon the towns of Ashland, Oregon, and Cedar City, Utah, to gorge themselves on Shakespeare brilliantly brought to life in faux Elizabethan theaters set down among the forests of the Pacific Northwest and the red rock canyons of the Southwest. Scattered over the West as well are productions aimed more at local audiences, such as the Colorado Shakespeare Festival in Boulder and the Grand Canyon Shakespeare Festival in Flagstaff, Arizona. In Boulder, you can spend a summer’s evening picnicking on a wide lawn and then wander into a Greek-style amphitheater hewn out of local red stone. As the sky deepens to sapphire edged by the strange, stark shapes of the Flatiron Mountains that loom behind the set, you can be swept away to some far country on the tide of Shakespeare, sharing the laughter of a thousand Coloradans as Beatrice baits Benedick, or shivering with the hiss of indrawn breath as Romeo forever drinks poison a scant moment too early to see that Juliet still breathes.

Colorado Shakespeare Festival, Boulder

But here, as I listen to the crowds dispersing downhill through the trees, the laughter and the sorrow are tinged with surprise: that Shakespeare is here, that it is so good, that they have enjoyed it so much. In the frontier West, the fact that Shakespeare tells good stories, and that those stories should be told well in the West, was no surprise at all — at least not to Westerners. From Jim Bridger, to the forty-niners, to the cowboys, the old wanderers would hardly recognize anything in the modern cities that rise on the plains and mountains, strung out like glittering beads along the Interstate freeways. Yet they might recognize and be glad of one thing on such a summer night: Shakespeare still plays well under Western skies.

© 1998 by Jennifer Lee Carrell

All Rights Reserved

Originally published in the Smithsonian, vol. 29, number 5 (August, 1998): 98-107.

Image of Shakespeare in a cowboy hat courtesy of Northwest University Drama, Seattle

I have really enjoyed the novels of JL Carrelll. I think her research of’How the Bard Won the West’ is a marvellous piece of research and writing.